The Great Reallocation: How $2.5 Trillion Left the Fed Without Breaking Markets

Between mid-2023 and early 2025, a staggering ~$2.5 trillion quietly vanished from a key Federal Reserve facility. This cash hoard, held in the Fed’s Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) facility, had ballooned after the pandemic, serving as a parking lot for money market funds (MMFs) awash in liquidity. Its rapid decline sparked fears of a “liquidity drain” that could destabilize markets.

Yet, nothing broke. Stocks remained resilient, and core funding markets, the essential plumbing of the financial system, stayed placid. This wasn’t a story of disappearing liquidity, but rather a massive and orderly asset reallocation. Here’s how it happened and why the system didn’t crack.

The Setup: A Reservoir of Cash

The ON RRP’s massive balance was a direct result of post-pandemic stimulus. Trillions in fiscal and monetary support flooded the system, but commercial banks, facing regulatory constraints, had little appetite to absorb it all. MMFs, unable to find better options, parked their excess cash at the Fed, which offered a safe, risk-free return. The ON RRP became a crucial release valve, swelling to over $2.5 trillion.

The Catalyst: The T-Bill Deluge

The great reallocation began in mid-2023 after the U.S. debt ceiling crisis was resolved. The Treasury, having run down its checking account (the Treasury General Account, or TGA) to fund the government, needed to rebuild its cash buffer—fast. To do this without disrupting longer-term bond markets, it unleashed a deluge of short-term Treasury bills (T-bills).

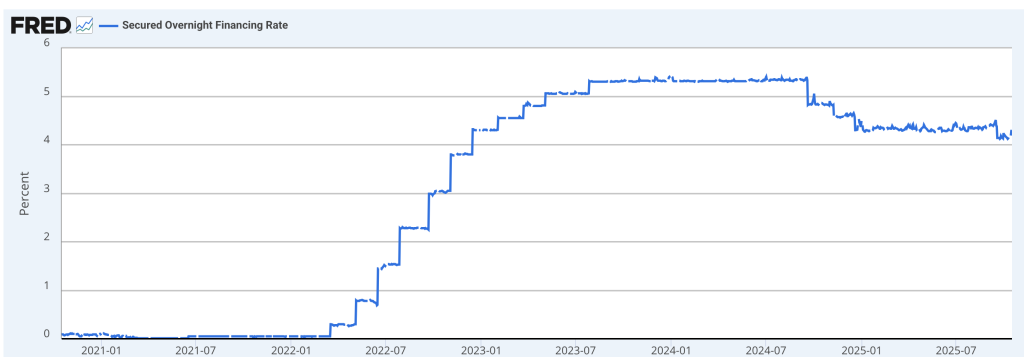

This sudden, massive supply of new T-bills forced their yields to become more attractive. For the first time in years, a clear and persistent yield premium emerged: newly issued T-bills began paying more than the Fed’s ON RRP facility.

The Trade: Money Market Funds Make Their Move

For the MMFs managing trillions in cash, this created a simple and compelling trade. Why lend to the Fed overnight for one rate when you could lend to the U.S. Treasury for a higher one?

They responded rationally, systematically pulling cash from the ON RRP and using it to buy up the higher-yielding T-bills at auction. Data from the Investment Company Institute shows a clear shift in MMF portfolios during this period, with holdings of Treasury securities rising as their ON RRP usage plummeted. This asset substitution was the direct mechanical driver of the drain.

Why Nothing Broke: Buffers and Backstops

The financial system remained stable for two key reasons, both rooted in the post-2019 monetary policy framework.

- A Liability Swap, Not a Liquidity Drain: From a balance sheet perspective, the transaction was elegant. As an MMF moved cash from the ON RRP to buy a T-bill, the Treasury deposited that cash back at the Fed in its TGA. On the Fed’s books, one liability (ON RRP) went down, while another (TGA) went up. This meant the ON RRP acted as a “sacrificial buffer,” absorbing the shock of the Treasury’s cash rebuild and shielding the commercial banking system’s core liquidity—bank reserves—from a sudden, sharp contraction.

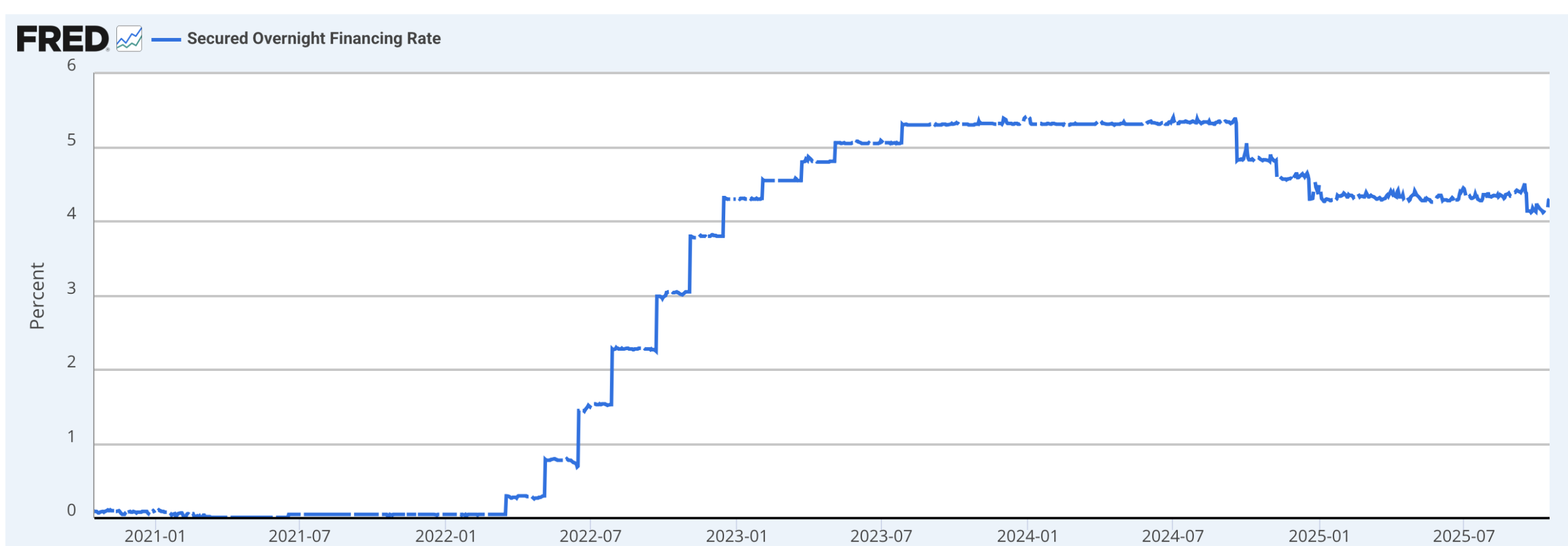

- The Psychological Safety Net: The Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) served as a powerful psychological backstop. The SRF acts as a ceiling on short-term funding rates, guaranteeing that eligible banks can always borrow cash from the Fed against Treasury collateral. Its mere existence assured markets that a 2019-style repo crisis was not a credible threat, preventing the kind of precautionary cash hoarding that can trigger a real liquidity crunch. Market health indicators confirmed this stability: the SOFR remained well-behaved, and repo settlement fails remained low.

What’s Next: Life After the Buffer

The uneventful drain of the ON RRP is a testament to the resilience of the Fed’s modern policy toolkit. However, with this massive liquidity buffer now depleted, the system is entering a new phase. Any future liquidity drains—from continued Quantitative Tightening or another expansion of the TGA—will now fall directly on bank reserves. The market’s transition to this new reality, where bank reserves are once again the marginal source of liquidity, will be the critical dynamic to watch for any future signs of funding pressure